Episode 219

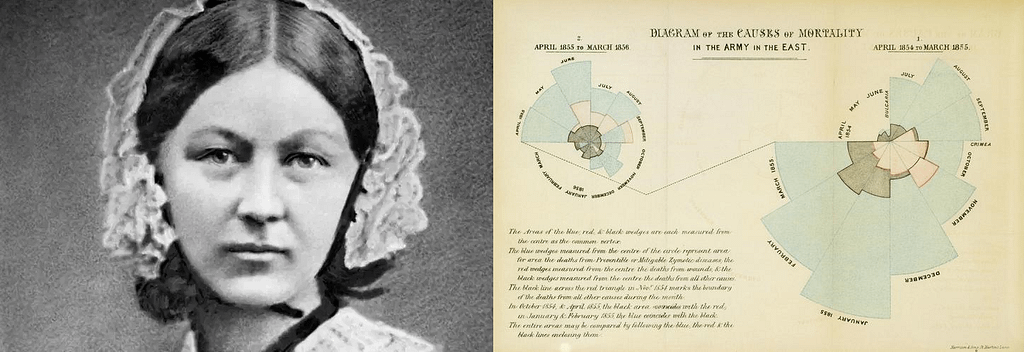

Up to the 18th century, making and trading things was harder than it needed to be. You had to deal with a bewildering patchwork of local constants and norms. It was actually the French Revolution & administrators who came out of it that started to codify how we measure things. The standards they adopted were ultimately formalized in 1875 at a Convention whose name you may recognize, the Metre – or should I say Meter – Convention.

The Standard set at the convention spread beyond France to most of Europe, removing friction in commerce and everyday life. Engineers could spec parts to the same tolerances; pharmacists could dose reliably across borders; food producers could print consistent nutritional labels; shipbuilders and container makers could agree on common dimensions; and architects and builders could order materials that matched on site. Over decades that shared language of measurement turned local guesswork into dependable infrastructure for industry, science and trade. Today, About 95% of the world’s population lives in countries that have officially adopted the metric system.

“Metric” in that sense solved disagreement about how much — it replaced local guesswork with a shared language of measurement so engineers, traders and regulators could trust one another.

Businesses face the same problem today — only the units have changed. Instead of metres and kilograms, modern organizations trade in clicks, sessions, impressions, cost, conversions and revenue. These are the metrics that power decisions, budgets and boardroom arguments. If one team’s “conversion” counts form submissions, another’s counts purchase intents, and a third’s counts paid signups, you get the same mess Europe lived with before standardization: wasted effort, mistrust, and bad decisions.

That’s why the digital-era equivalent of adopting the metric system matters: a single, governed vocabulary of business metrics (clear definitions, lineage, owners and calculational rules). Give everyone the same definition of “revenue,” “LTV,” or “ROAS” — and the same ability to trace where those numbers came from — and you turn noisy arguments into aligned action. In short: standardize the units, restore trust in the numbers, and your dashboards start to behave like the modern factories that metrication once enabled for Europe.

Turn to how many marketing teams are now constrained by the disparate marketing measures we have – it’s the choke-point preventing us from sharing dashboards between groups, asking bigger questions, and getting full bang for money spent on our analytics infrastructures. If we’re going to keep our sanity, we must get on with Metricizing our metrics. Going down a path where business metrics are treated as standardized units opens up possibilities as big as the Metric System opened up for our global economy.

Our guest is a Proud Swiss-Canadian, technologist and entrepreneur. In 2001 he co-founded analytics software company Klipfolio, one of whose products aims to address metric management. Note that I’m having him on today to give his personal perspective – there’s no sponsor or affiliate relationship here. When he’s not working in or talking about analytics, you’ll find him cycling in the city we both call home. Let’s go talk to Allan Wille.

Timestamp Chapters

0:00:00 Standardizing Digital Metrics: A Modern Metric System

0:03:44 The Spreadsheet Era: Data Insights and Hidden Dangers

0:07:43 Leveraging APIs for Consistent and Mature Data Pipelines

0:11:39 Why Data Governance is Crucial for Trust in Metrics

0:19:29 Elevating Metrics: From Raw Data to Business Contracts

0:25:14 Bridging the Gap: Metric Catalogs for Data Teams

0:29:49 How AI is Standardizing Metric Definitions and Trust

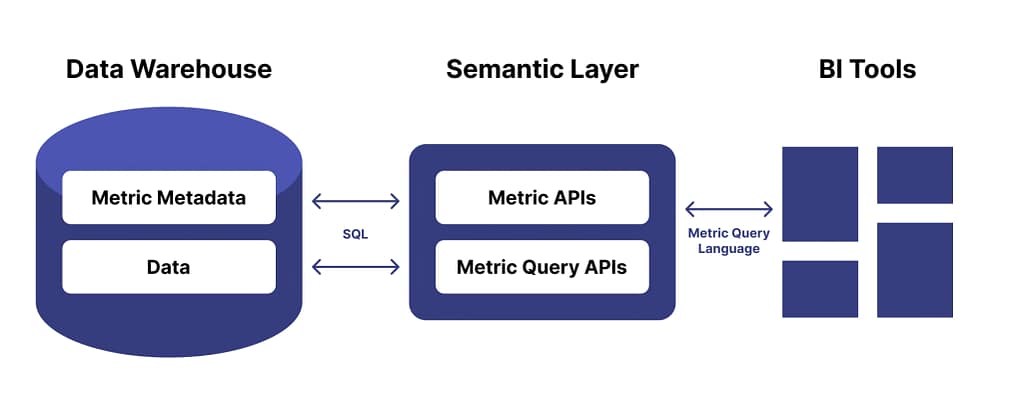

0:37:44 Navigating Data Architecture: Semantic Layers and Power Metrics

0:44:26 Finding Your North Star: Metrics for Business Success

People, products or concepts mentioned on the show:

The meaning of Ontology is found in the Definition section of this blog.